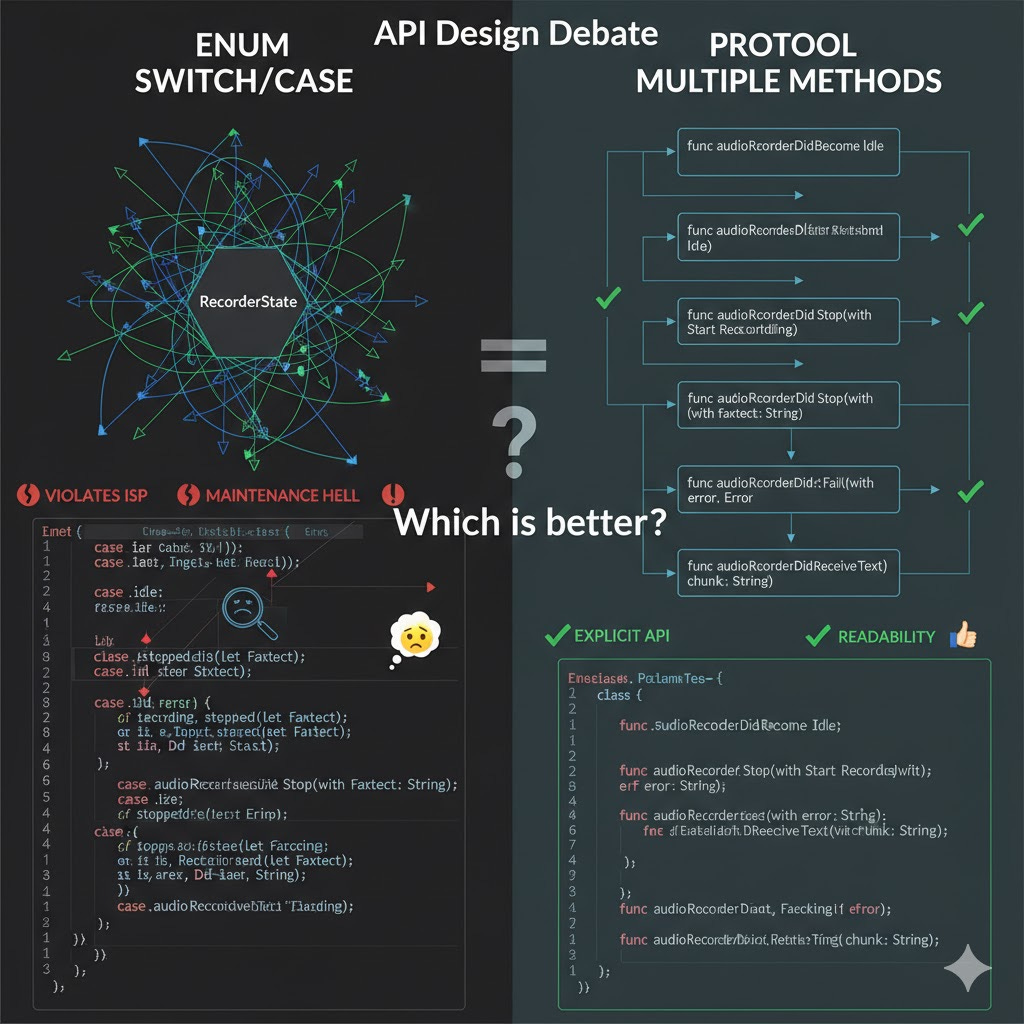

Enum Switch/Case vs. Protocol with Multiple Method Calls

There is so much dogma in the iOS community. Enum based protocols with lots of switch/casing considered to be good where, most of the time a more straightforward message sending/delegate would suffice

In my development career, I jumped around different languages and platforms. Everything from Objective-C on iOS (and later Swift), to Java on Android (and later Kotlin), to Ruby on Rails and lately Typescript/Node, and a bunch of things in between (Dart before Flutter days), and more.

I saw different pros and cons and strengths and weaknesses that each language, framework, pattern, or community exhibits. At the end of the day, I wasn’t able to find a community, pattern, convention, framework, or language that fully satisfies me and my sense of what is good code or bad.

What I ended up doing is picking “the good parts”—different bits and pieces, conventions, approaches, etc.—from each one of those different languages, frameworks, and communities and mixing them together in whatever language or platform I happen to use and write code for at the time. It actually turned out pretty well and at the end of the day is grounded in SOLID principles and Clean Code/Clean Architecture which are all language, framework, and community agnostic.

So given all that, it might not be surprising that I find some (if not a lot lol) parts of Swift and Swift community conventions odd or pointless or wrong. For example, the other day, I was reviewing some code in an iOS project that had to deal with connecting to a voice audio recording library. It was already implemented in our codebase and I had to take a look at its API to understand how to use it and at the current usage of it across the codebase.

My assumption was—well, there is probably some wrapper object around the library’s class/object that abstracts out starting, pausing, and stopping the recording. And I assumed there would be some sort of a delegation (via protocol, or callback closures, or a stream of data) happening upon recording start to “stream” the recorded data/voice/text as it happens. And sure enough it was; both of those assumptions were correct but the data streaming/delegate/callback part gave me a pause.

Here’s how the API looked like:

enum RecorderState {

case idle

case recording

case stopped(finalText: String)

case failed(error: Error)

case receivedText(chunk: String)

}

protocol AudioRecorderDelegate: AnyObject {

func audioRecorder(didChangeStateTo state: RecorderState)

}

protocol AudioRecorderProtocol {

var delegate: AudioRecorderDelegate? { get set }

var currentState: RecorderState { get }

func start()

func stop()

}

final class AudioRecorder: AudioRecorderProtocol {

weak var delegate: AudioRecorderDelegate?

private(set) var currentState: RecorderState = .idle

func start() {

self.currentState = .recording

delegate?.audioRecorder(didChangeStateTo: currentState)

}

func stop() {

let finalText = “Final transcribed text here”

self.currentState = .stopped(finalText: finalText)

delegate?.audioRecorder(didChangeStateTo: currentState)

}

// ... more business logic to update currentState and notify delegate about recording process

}Everything is pretty straightforward, and the usage of it looks like this:

final class ViewModel: AudioRecorderDelegate {

private var audioRecorder: AudioRecorderProtocol

var onStateChanged: ((RecorderState) -> Void)?

init(audioRecorder: AudioRecorderProtocol = AudioRecorder()) {

self.audioRecorder = audioRecorder

self.audioRecorder.delegate = self

}

func startRecording() {

audioRecorder.start()

}

func stopRecording() {

audioRecorder.stop()

}

func audioRecorder(didChangeStateTo state: RecorderState) {

switch state {

case .idle:

// do stuff

break

case .recording:

// do stuff

break

case .stopped(let finalText):

// do stuff

break

case .failed(let error):

// do stuff

break

case .receivedText(let chunk):

// do stuff

break

}

}

}At first glance any Swift developer would say - “Alex, I see nothing wrong about this. There is an enum with all the states, this is very Swifty!” And yes, this seems to be the pattern that the Swift community fancies - to pass all the possible states/scenarios like this via a callback in one property and to declare an enum that lists all the possible cases. I acknowledge that there are good parts to this - for example, you get the compiler time safety when you add new states/cases to this enum. The compiler will warn you and make you explicitly handle all of them.

For any Swift developer this would be just it - the dogma says that this is good and this is how it should be.

But the problem is this approach makes your API less explicit and breeds the switch/case ifelsing across your codebase. The more new enums you add the more cases in the switch you’d need to have, especially if you pass that enum value around in different parts of your code.

And on top of it, the worst issue is that this makes your API readability much worse - it is very hard to say at a glance what it does, what kinds of callbacks would you receive if you are the delegate of this audio recorder. All you get is just this one method declaration: func audioRecorder(didChangeStateTo state: RecorderState) in AudioRecorderDelegate. You have to now hunt down for the enum RecorderState declaration (hopefully it’s in the same file, but likely it won’t be, because reasons lol) to actually understand what the API is. And imagine if you had several callback methods like this in AudioRecorderDelegate and each one of them had their own set of enums with their own 3-5 cases - you multiplied the problem of this “treasure hunt for the API declaration” tenfold!

Bottom line, even though the Swift community loves it, this approach breaks SOLID principles and makes your API implicit, indirect, and scattered.

A better approach is to stick to a more generic, tried and true, OOP/SOLID principles approach of sending messages and explicitly declaring your API as a set of dead simple callback methods:

protocol AudioRecorderDelegateV2: AnyObject {

func audioRecorderDidBecomeIdle()

func audioRecorderDidStartRecording()

func audioRecorderDidStop(with finalText: String)

func audioRecorderDidFail(with error: Error)

func audioRecorderDidReceiveText(chunk: String)

}

protocol AudioRecorderV2Protocol {

var delegate: AudioRecorderDelegateV2? { get set }

func start()

func stop()

}

final class AudioRecorderV2: AudioRecorderV2Protocol {

weak var delegate: AudioRecorderDelegateV2?

func start() {

delegate?.audioRecorderDidStartRecording()

}

func stop() {

let finalText = “Final transcribed text here”

delegate?.audioRecorderDidStop(with: finalText)

}

// ... more business logic to notify delegate about recording process

}And the consumption now looks like this:

final class ViewModelV2: AudioRecorderDelegateV2 {

private var audioRecorder: AudioRecorderV2Protocol

var onIdle: (() -> Void)?

var onRecordingStarted: (() -> Void)?

var onRecordingStopped: ((String) -> Void)?

var onRecordingFailed: ((Error) -> Void)?

var onTextReceived: ((String) -> Void)?

init(audioRecorder: AudioRecorderV2Protocol = AudioRecorderV2()) {

self.audioRecorder = audioRecorder

self.audioRecorder.delegate = self

}

func startRecording() {

audioRecorder.start()

}

func stopRecording() {

audioRecorder.stop()

}

func audioRecorderDidBecomeIdle() {

// do stuff

onIdle?()

}

func audioRecorderDidStartRecording() {

// do stuff

onRecordingStarted?()

}

func audioRecorderDidStop(with finalText: String) {

// do stuff

onRecordingStopped?(finalText)

}

func audioRecorderDidFail(with error: Error) {

// do stuff

onRecordingFailed?(error)

}

func audioRecorderDidReceiveText(chunk: String) {

// do stuff

onTextReceived?(chunk)

}

}The AudioRecorderDelegateV2 declaration is very straightforward and tells you everything it does at the first glance:

protocol AudioRecorderDelegateV2: AnyObject {

func audioRecorderDidBecomeIdle()

func audioRecorderDidStartRecording()

func audioRecorderDidStop(with finalText: String)

func audioRecorderDidFail(with error: Error)

func audioRecorderDidReceiveText(chunk: String)

}There is no ambiguity, there is no hunting for other declarations, it’s just all there, explicit as simple messages to be sent from one object to another.

There is also still the same benefit of compiler time safety - if you add another method to the delegate declaration about a new event happening, everyone who adopts that protocol will get a compiler time warning and will have to implement it, just like with the enum case.

This instantly reduces the amount of ifelsing/switch-casing across your codebase and makes skimming and understanding your API dead simple. And, I’d argue, especially so when using LLMs nowadays. On top of it, it reduces the temptation to breed state and pass along the enum for other parts of the code to figure out what to do with each switch/case.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the difference between the two approaches boils down to Enum State Machine approach vs Event Emitter approach.

The “Swifty Enum State” approach is a great tool for modeling objects whose internal state needs to be guaranteed (e.g., a Result type, or a single state machine within a component).

However, when designing an API that is purely meant to act as an Event Emitter—sending asynchronous messages about changes—the traditional, multi-callback approach remains the superior choice for maintainability, simplicity, and adherence to the Interface Segregation Principle. It is cleaner, more readable, and respects the fact that your consuming ViewModel is the true gatekeeper of your application’s state.

We should embrace the flexibility of well-designed interfaces, rather than defaulting to monolithic enum structures just because the Swift language makes switch statements easy.

I guess I'm on the "enum" side for a couple of reasons (some of which may or may not happen eventually):

The callback looks nice for an Event Emitter. Downside is, there are two states now. One internal state of the recorder and then a state you need to track within the consumer of that recorder. Now the app is responsible for correctly tracking all state changes - which absolutely can be done, but requires you to actually do that.

However, once you want to just query the state of the Event Emitter you are screwed (I could imagine some sort of shared resource), as you only get an Event on state change. Just my belly feeling, but this smells less robust to me.